Finally, the summer holiday is here! I’m going to spend it dyeing (with natural dyes, of course), knitting (with my naturally dyed yarn) and reading (about natural colors, what else??).

I just finished reading the Norwegian book “Vaid – En historie om blått” (Woad – A History of Blue) by Anne Sagberg, a well written and interesting book that contains a lot of information that was new to me. The author obviously did her own research instead of rehashing existing literature on this topic.

The chapters on historical finds of woad dyed Norwegian textiles are especially interesting. Wild-growing woad is found in multiple locations in Norway, including the coast of Nordland (quite far North). It’s unknown if it was previously grown for dyeing, but there are many finds of woad dyed textiles from different eras.

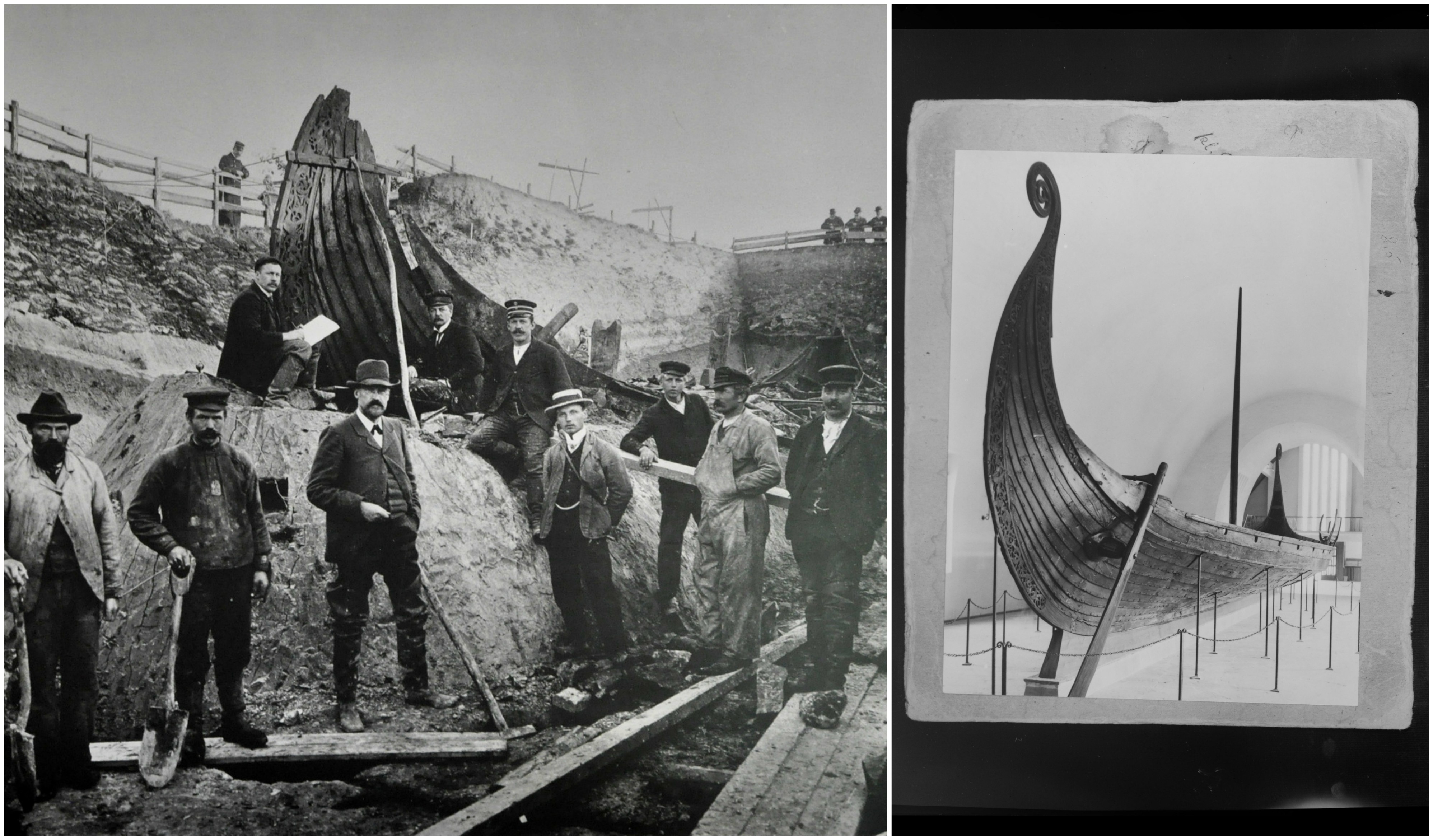

The Oseberg Ship was discovered in 1904, and is a ship grave from the year 834. Two women were found in it – one dressed in blue, on in red. The red textile is very fine, probably imported, and the garment is embellished with silk ribbons. The woman in red is referred to as the Oseberg Queen. The blue textile is not as fine, probably a local product, so the woman in blue could be a servant.

Not only was the blue textile dyed with woad, the queen also had a small box of woad seeds with her among the grave gifts. I find this really interesting. We don’t know if the plant was cultivated in Norway at the time, but someone almost 1200 years ago found a small box of woad seeds precious or important enough that it was given to an important woman to bring with her to the afterlife.

I saw the Oseberg Ship, which is found at the Viking Ship House, some years ago. It’s impressive and beautiful, but unfortunately, I don’t remember anything about a box of woad seeds. I didn’t know to look for it at the time, but also, I don’t know if it is displayed.

The Baldishol Tapestry is a surviving fragment of a once-larger piece – you can tell from its torn edges. Its story is incredible.

In 1879, the old church in Baldishol was torn down, and the neighbors bought some of the objects from the church. Some years later, a Louise Kildal visited from Oslo and took one of the objects home with her – a dirty rag that the organist used to drape over his legs because there was a terrible draft in the old church (!)

Home again, Louise Kildal washed the rag, and what came out? The colorful Baldishol Tapestry, a wowen picture from between 1040 and 1190. The tapestry is kept at Kunstindustrimuseet in Oslo, and next time my path goes near it, I’ll make a point of seeing it.

Meanwhile, I could easily see myself dyeing some yarn to match the tapestry’s colors. It contains several blues, probably from woad. The green color is yellow overdyed with blue, so clearly large amounts of blue went into creating this precious piece. One of the red threads (left over from earlier restorative work) was analyzed in 2013. The analysis showed that the red color comes from a member of the Rubiaceae family (to which madder belongs) but apparently couldn’t tell if the color is indeed from madder or another member of the family. The yellow has not yet been analyzed, but Anne Sagberg tells us that weld was used since early times, and could have been cultivated in Norway or imported.

The book covers many more topics than the ones I mention here. Anne Sagberg writes about the excavation of a grave inside the stave church of Uvdal. A young woman was buried there in the latter half of the 14th century, wearing a woad dyed hood, a shape that was very fashionable at the time. Sagberg recounts the problems she encounted trying to recreate the hood (not easy!). A detailed description is also given to three wall hangings, Vossaduken, Huldreduken and Veøyduken. They are from the late 15th century, and all embroidered with geometric patterns that I’d like to knit one day.

Anyone who made it through all this text will have no doubt that I’d like to recommend Sagberg’s book to those able to read Norwegian!

[…] Read this post in English […]